Published on: 30/07/2025 · Last updated on: 05/11/2025

Introduction

The Office for Students (OfS) General Ongoing Conditions of Registration under B4.2 condition demand that a University must ensure that:

- students are assessed effectively

- each assessment is valid and reliable

- academic regulations are designed to ensure that relevant awards are credible.

In this context, a valid assessment is an assessment which is valid for a specific purpose and allows students to demonstrate attainment of the learning outcomes addressed by the assessment. In short, a valid assessment evaluates what it is supposed to. This works alongside assessment reliability, which requires that assessments and marking criteria are designed to ensure that evaluation of the relevant learning outcomes is consistent from student to student, marker to marker, and year to year.

A key risk to ensuring the validity and effectiveness of assessments is the security of an assessment task – in other words, how susceptible it is to student’s ‘cheating’ and thus how sure we can be that students have met the learning outcomes of their course. Taken together, assessment validity and security form two pillars of academic integrity.

For closed book assessment, such as exams, security is ensured through invigilation and/or in-person observation. For open assessment, such as coursework, this is more challenging. Key education thinkers on academic integrity, such as Philip Dawson, argue that cheating is just one aspect of assessment validity, that should not pull focus from important conversations around learning and fairness, which are upheld through effective assessment design. It is through focusing on assessment design that we will be best placed to assert that our graduates meet the standards we endorse.

This article addresses how effective assessment design can ensure the validity of open assessment. It begins by outlining the importance of taking a course-wide approach to managing risk around academic integrity, before outlining important considerations when designing individual assessments: to pinpoint the knowledge or skills you are intending to test, and whether there are ideal processes you wish your students to undertake to complete their assessment. This interrelates closely with the selection of valid assessment types and assessment categorisation as regards the use of GenAI. The second half of the article looks at how to promote completion of your assessment through the desired route(s), by anticipating deviations in process; building in assessed milestones, and using marking criteria and feedback to set and reinforce expectations. A brief annotated list of useful resources from the sector is included at the end.

A Course-Wide Approach: The ‘Swiss Cheese Model’

No assessment – even exams – can be wholly proof against academic misconduct. Accordingly, we advocate that students be assessed by a suite of different assessment types across their course, which test a student in the round. This is an application of the ‘Swiss Cheese model’, developed as a method of managing risk and originally propounded by James T. Reason. The application to assessment design was one suggested by Phillip Dawson, who argued that, like a slice of Emmental cheese, any single assessment will have ‘holes’ in it – areas of vulnerability that risk exploitation (inadvertent or otherwise). By layering different assessment types – the slices of cheese – the hole in one assessment type is ‘patched’ by another. For example, a strength of individual coursework assessment is that it allows students the time to develop a deep understanding of a topic and to take their time in writing and editing. However, the risk is that students plagiarise, collude, or even engage in contract cheating. An in-person oral exam plugs those ‘holes’ since it takes place in real-time; however, it has other risks in that it will disadvantage those who suffer with anxiety, as well as those who find it difficult to spontaneously verbalise their thoughts.

Having emphasised the importance of assessments working in concert, there are steps that can be taken when designing single assessments that can help promote academic integrity and minimise the chance of academic misconduct.

Target Knowledge/Skills and Ideal Routes to Assessment Completion

Once you are aware of the course context in which you are setting your assignment, it is important to carefully consider your target knowledge and/or skills, i.e. what you are intending to test through your assessment. The knowledge and skills you identify should align with the intended learning outcomes at unit and course level. It should also be clear how your assessment connects to the other assessments your students will undertake across their course. Refer to your course assessment map where available.

In designing an assessment, it is also useful to consider the process students might undertake to complete the assessment. In other words, what kind of tasks will the assessment require students to complete? What cognitive or physical tasks must they perform? Are all of these integral to the assessment?

How students approach an assessment will very much depend on the characteristics of the cohort, as well as the teaching and learning methods they have been used to on their course. In conceptualising a student’s ideal route to completing an assessment, remember also to accommodate for common difficulties students with disabilities might have. Under the Equality Act 2010, Universities have an anticipatory duty to make reasonable adjustments to education for students with disabilities. An anticipatory approach means proactively considering likely barriers to learning for such students and what reasonable adjustments can be put in place in advance to address these, as well as having processes in place to support further individual adjustments where required (e.g. Disability Action Plans). More information can be found here: AdvanceHE, 2025 and on the University’s Inclusive Education Project Sharepoint site.

Appropriate Selection of Assessment Type

When considering the process you wish students to follow, this inevitably leads to consideration of assessment type. One way of viewing the selection of assessment types is choosing amongst a variety of oppositions:

| Exam | <————————————-> | Coursework |

| Closed book | <————————————-> | Open book |

| In person | <————————————-> | Remote |

| Verbal | <————————————-> | Written |

| Individual | <————————————-> | Group |

At first glance, it may seem that the options in the first column provide the most robust method of upholding academic standards, since they offer more control over variables; however, the reality is more nuanced. Where knowledge-recall is the central goal of an assessment it may well be most appropriate to lean to the left of each of these dichotomies; however, there is arguably more ‘real world’ validity in assessments that sit on the right of the scale, in other words, they more closely mirror the world we live in and therefore it can be argued that students who do well in these assessments are better prepared to apply their skills in contexts beyond their course. Assessment types high in ‘real world’ validity include competency-based and authentic assessments that address or simulate real-world problems and test students on their application of knowledge.

In selecting assignment type, it is also important to remember that each student will have a different profile of strengths and weaknesses: some may excel in high stakes exams, where others thrive undertaking research over a period of time. It creates an unfair and misleading snapshot to cater purely to the strengths of one group.

Professional, statutory and regulatory bodies may also be a useful source to draw upon when choosing assessment type. The QAA has recently updated its Subject Benchmark Statements to include reference to GenAI and its impact on learning and assessment. For example, their updating of their Accountancy Subject Benchmark Statement emphasises the need for Accounting degrees to

adapt dynamically […] moving away from assessment that relies on rote learning, regurgitation and surface learning [and toward…] critical assessment, including authentic scenario and case-based work; embedding technical problem questions into dynamic cases or scenarios […] assessing students’ critical understanding of the implications of AI within accounting as a discipline (pp. 12-13)

This gives a strong steer as regards the need to pivot to GenAI-responsive forms of assessment.

Lastly, it is important to consider the role of assessment in learning itself. For example, whilst group work may be a method of assessment it is also an important tool for developing self-awareness and negotiating skills. It also helps prepare students for employment and provides them with rich examples they can draw upon in selection processes.

For all the reasons cited here it is important that a variety of assessment types are deployed across a course.

Allocating a GenAI Assessment Categorisation

Also central to considerations of process, is whether and to what degree you wish your students to use GenAI. To minimise academic misconduct, it is essential that students are given clear instructions regarding acceptable and desirable processes to follow when completing an assessment, and that is especially true of the use of GenAI. As emphasised in the LSE Student Manifesto on AI, it is also important to provide a clear rationale behind your instructions and for those instructions to be realistic. For example, it is arguably unrealistic to stipulate students not use GenAI at all when researching, since many browsers now automatically return AI answers in response to searches.

At the University of Bath, to help students understand whether and how GenAI should or could be used, it is required that each assessment be labelled as Type A, B, or C. Assignment brief templates, with a section on assessment categorisation, can be found here.

| Type A | Type B | Type C |

| Where you wish your students to demonstrate knowledge and skills without the assistance of GenAI your assessment should be Type A. In most cases, to be robust, these must be invigilated and closed-book. | For Type B assessments you should make clear the specific purposes for which students are permitted to use GenAI and ideally the task should be designed in such a way that only those uses would be practical or advantageous for students. | Where you have knowledge or skills to impart on your course for which GenAI is integral, for example because GenAI has a specific usage in the industry your graduates often enter into, it is appropriate to set a Type C assessment. An example of this would be asking students to produce or edit an image using GenAI. For ideas on incorporating GenAI into your teaching, you may be interested in the work of Dr. Ioannis Georgilas. |

We recommend that on any given course students should be encouraged to learn about the strengths and drawbacks of GenAI in their disciplinary context. One way to do this might be to have at least one assessment that is Type C. The other assessments should be split between Type A and Type B. The precise balance of this will depend on the course, with more theoretical disciplines likely to have a greater preponderance of Type A assessments, while more practical disciplines will likely utilise more Type B assessment.

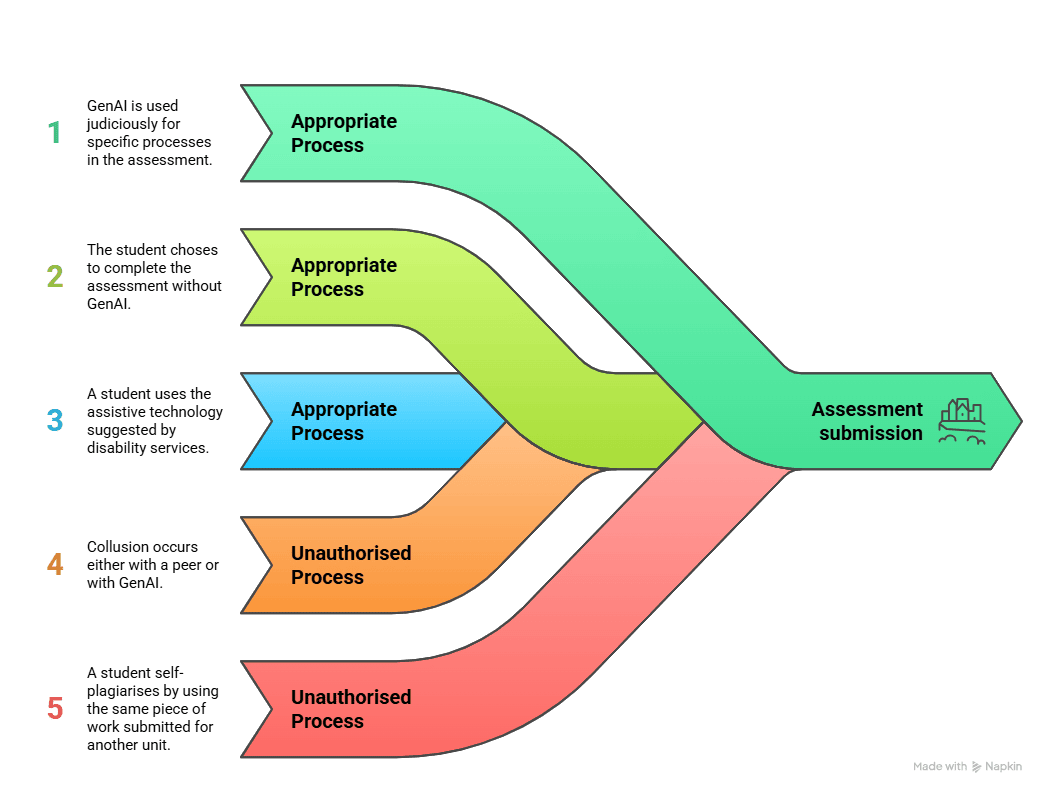

Type B assessments grant the greatest degree of freedom to students in terms of possible processes for completion. Some may choose not to use GenAI in completion of their assessment, whilst others may choose to do so. Additionally, Type B assessments will often be coursework and, therefore, completed without supervision. For these reasons lecturers are often most nervous about upholding academic integrity in assessments of this type; however, careful design of Type B tasks can help to reduce the probability that students will feel tempted into academic misconduct through colluding with or plagiarising GenAI.

A well-designed Type B assessment is likely to have one or more of the following characteristics:

- it is complex and comprised of inter-related elements, requiring demonstration of ‘original analysis [and] deep conceptual understanding’ (LSE Student Manifesto on AI);

- it has a strong emphasis on context and the application of knowledge, which may involve working with a context which is unavailable to GenAI, e.g. relying on data gathered through in-person interactions;

- it contains a reflective element that asks students to track the process undertaken in completing the assessment, e.g. asking groups to fill out a log;

- it invites students to select from a range of possible tasks. If students can choose something that interests them they are more likely to be intrinsically motivated and will therefore be less tempted to misuse GenAI;

- it has check-in points, or assessed milestones, that help ensure students are following the desired process(es).

Promoting Preferred Routes

In order to encourage students to follow the most desirable routes to assessment completion, it is important to explore the deviations from these ideal routes that may be available to students. In other words, what are the risk to the validity of your assessment. Can students short-circuit the cognitive tasks you intend them to undertake? For example, if students are sitting a digital exam and do not use a locked-down browser they may be able to find answers to the questions online. Similarly, GenAI can greatly shorten the time taken to produce traditional coursework essays, by undertaking research on behalf of the student, identifying arguments and structuring an answer.

Familiarising yourself with the GenAI tools that might be used to complete assessments in different media and/or in your discipline context will help you imagine the different processes students might follow. CLT has prepared some self-paced resources to help you broaden your knowledge in this area. For a more bespoke discussion contact tel@bath.ac.uk.

If the process the student follows in completing the assessment is important for enriching and/or testing their learning, identifying those milestones and setting intermediate assessed goals (whether formative or summative) creates guardrails that help ensure students follow the intended process. For example, as part of a coursework research task you could ask students to produce a reflective note alongside an annotated bibliography that outlines how they found their sources. See this example created by Dr Dai Moon:

Be open with students about why these milestones are in place. Setting clear expectations with students regarding how they should complete their assessment task, will help minimise inadvertent breaches of our academic integrity policy.

Examples of Different Processes Followed to Complete a Type B Assessment

Focus of Marking Criteria and Feedback

In setting an assessment a tutor opens a dialogue with their students. The framing of the assessment brief – and the marking criteria, which should be transparently shared with students – will influence how students channel their efforts. In the age of GenAI it is particularly important that the marking criteria and their weighting favour the demonstration of human critical thinking skills, whether that be the ability to reflect, show contextual understanding or problem solve. That scene setting, that begins with the assessment brief and marking criteria, should be carried through and reflected in the eventual feedback supplied to students.

Feeding back on a student’s work is an opportunity to reinforce your expectations around standards not only as regards the assessment they have just completed, but of the assessments they will go on to complete later in their course. We therefore recommend that the feedback you give is future-focused and actionable, that is, the students are given examples from their current assessment regarding what they have done well or badly and they are given advice on how to improve in their next assessment.

When designing assessment for first-year undergraduates, or for students who come from a very different culture of assessment, it is particularly important to build in formative assessment points and then use those opportunities to communicate where students might be risking an accusation of academic misconduct. For example, if many of your students are not referencing properly, you might give cohort-level feedback on how to avoid plagiarism. If the problem is more localised it may be appropriate to have private one-to-one conversations with the students involved. Where students have infringed our academic integrity policy for summative assessments please refer to our academic misconduct policy.

Final Thoughts

It is important to review the robustness of your assessments over time as this may change for a number of reasons. Firstly, assessment redesign might be prompted by developments in GenAI, as this may open up new avenues in terms of how assessments can be completed. Secondly, there may be changes to the cohort profile, such as an increase in students from different assessment cultures or those with a particular disability or specific learning difference. It is important that adjustments are made to accommodate these students as they may otherwise be at higher risk of committing academic misconduct. It is through considering the needs of our students that we will be best placed to design robust assessments that enable our students to demonstrate the full range of their abilities.

To discuss any of the issues raised in this article please contact Ellie Kendall or Abby Osborne.

Further Resources:

Professor Phill Dawson of Deakin University on Assessment and Swiss Cheese: AI Education Podcast: Assessment and Swiss Cheese – Phill Dawson – Episode 9 of Series 9

Association of Pacific Rim Universities Whitepaper on GenAI in Higher Education recommending collaboration between universities and with students https://www.apru.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/APRU-Generative-AI-in-Higher-Education-Whitepaper_Jan-2025.pdf

LSE Student Manifesto on AI: https://info.lse.ac.uk/staff/divisions/Eden-Centre/Assets-EC/Documents/PKU-LSE-Conf-April-2025/LSE-PKU-Student-Manifesto.pdf

Oregan State University’s updating of Bloom’s Taxonomy for the AI age: blooms-taxonomy-revisited-v2-2024.pdf

Conference presentation emphasising the importance of precision in assessment instructions, particularly for neurodiverse students, given by student, Deano Lund: Neurodiversity and the need for stable AI guidelines (16:15 minutes)

PowerPoint discussing using AI tools to provide reasonable adjustments for disabled students: Ros Walker AI in Assessments.pptx – Google Slides

Conference presentation summarising the University of Sydney’s approach to assessments: A “two lane” approach to assessment in the age of AI: Balancing integrity with relevance (14:41 minutes)

An approach to assessment by a University of Bath Computer Science Professor: Case Study: GenAI-adapted assessments – Prof Davenport

An example of integrating GenAI into teaching – Faculty of Engineering lecturer Dr Ioannis Georgilas: Case Study: Supporting students in using Generative AI – Learning and Teaching

A suggested approach from MIT about adapting students’ learning experience in the light of AI: 4 Steps to Design an AI-Resilient Learning Experience – MIT Sloan Teaching & Learning Technologies