Published on: 10/05/2024 · Last updated on: 02/09/2024

Dr Gosia Goclowska – Lecturer in Dept of Psychology

Interested in the idea of introducing more ‘real-world’ challenges into your teaching, but not sure how to go about it? Wondering how best to structure your unit to support collaborative groupwork? Read on about the approach used by Dr Gosia Goclowka in her final year elective unit for Psychology students.

Themes: flipped learning, mentimeter, groupwork, authentic assessment

Here’s a video of Dr Goclowska outlining her unit at Edufest in February 2024:

The two signal features of authentic assessment are firstly, a real-world problem and secondly, stakeholders who want to solve the problem. Primary considerations in setting authentic assessment are whether and how to put students into groups, how much time to allocate to the whole exercise and how much scaffolding or structure to provide. This case study is organised under those headings. For further information on the theory and practice of authentic assessment, refer to our guide here.

1. Real-world problem

Authentic assessments require students to work on a real-life problem, and in this one-semester final year elective unit students are asked to take on the mantle of a researcher working at a university. They must come together in groups of ideally 6 or 7 to identify a real-world problem that might benefit from further research with a budget of £2000. Their task is to complete a funding bid using a proforma based on a real grant application. The precise nature of the problem they choose is up to the students. Examples of topics chosen in the past include:

- Can doodling increase pupils’ creativity?

- Can art therapy tackle school children’s anxiety?

- How can we help students with ADHD thrive creatively?

- Why does mindfulness improve creative performance?

- Can ChatGPT increase the creativity of students’ writing?

2. Stakeholders interested in solving the problem

The second element of authentic assessment is that work is prepared for an audience, real or imagined, who have an interest in the problem discussed. The notional audience for the students is the research bid assessors and although students will have no contact with bid assessors, real or role-played, they are guided in their task by tutors who act as mentors. Their role is that of a senior colleague with experience of the research bidding process. By occupying this role tutors are able to infuse authenticity into their interactions with the students, giving sometimes surprising ‘behind the scenes’ advice to the students, such as that, when writing a bid application, accentuating the positive is sometimes a better approach than strict accuracy! Although the tutors will ultimately act as summative assessors, that is not the role they are playing during tutorials, and so students are invited to meet the requirements of a grant awarding panel rather than seek to satisfy the preferences and biases of their tutor.

3. Groupwork

A common element of authentic assessment is the need for collaboration, and groupwork is an integral part of Dr Goclowska’s unit. Let’s look at how she structures this component:

Group formation:

- At the beginning of the semester, students form groups. Self-selected groups have worked well with cohorts where students were already known to each other, but in other years when there have been more joint-honours students, pre-setting the groups to ensure an even spread of expertise has been more successful.

- During the first teaching session, students are given guidance on how to build a strong team. Firstly, they are asked to discover the expertise in their group. Some may have been on placement the previous year for example, and be able to draw on their time in industry.

- They are directed to draw up at least three ground rules, such as attending meetings.

- Finally, they are directed to set up a group communication channel, such as WhatsApp, to facilitate ongoing collaboration.

Fostering interdependence through ‘jigsaw learning’:

- Although groups do not need to pitch their initial ideas until week 5, the framework for collaborative working is scaffolded from the start by assigning students different readings to create interdependence on one another. This is a technique known as ‘jigsaw learning’, meaning different team members have different parts of the puzzle and so must come together to gain a full picture.

Addressing conflict:

- The conflict that has arisen has been minimal: Dr Goclowska estimates it has occurred in only around 5% of cases. One factor may be that this unit is elective, so only students comfortable with collaboration are likely to choose it. Another factors may be that only 20% of a student’s grade arises directly from groupwork (a group presentation on their research bid), while 80% is drawn from an individual write-up of that bid, meaning students are not as concerned as they might otherwise be about freeloading.

- Most complaints have been low level and anonymous and have been dealt with simply with reminders to the group to be mindful of the ground rules drawn up at the start.

(For further guidance on how to set up effective groupwork see CLT’s case study of two units in Economics and our guidance on effective groupwork. You may also wish to consider supporting technologies, such as Moodle marking, Feedback Fruits and Crowdmark – the latter two of which will need to be funded by your department, faculty or school.)

4. Timing

The unit takes place over a whole semester, with the task set and groups formed right at the start so that they have plenty of time to grapple with group dynamics, assimilate new knowledge, use it to crystallise ideas and then work out how to communicate these through their presentations and research bids. Students valued this, commenting:

‘being in our presentation groups from the begining [sic] was super helpful in bulding [sic] relationship[s] with them before we had to start properly working on our research proposal ideas and presentation’,

‘the consistent group work within this module really helped uni to feel less lonely.’

5. Scaffolding

Authentic assessment often allows a large degree of autonomy, and this is the case here in that groups are free to choose their own topic for the research bid, albeit in their first tutorial, for which they are required to pitch two different ideas, they may be encouraged more in one direction than another. This freedom reflects the positioning of this unit as a final year elective unit, where students have already built a good amount of expertise as well as the skills for independent study. Students appreciated this freedom, with one student commenting

‘I liked how there was lots of scope for us to explore our own interests in a research proposal :)’.

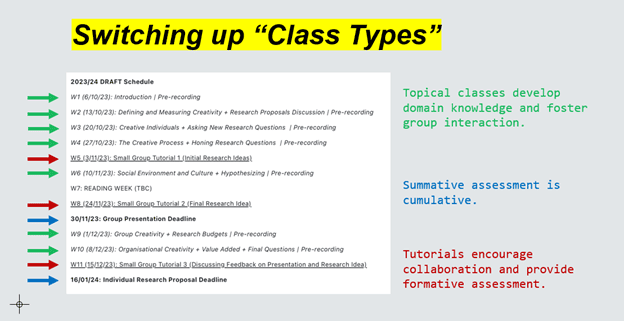

This is not to say the unit is without structure, however. As can be seen from the graphic below, careful thought has been given to sequencing, with topical sessions that cover domain knowledge clustered near the start of the unit. These are delivered through a model of flipped learning, whereby students watch or read material before attending the in-person sessions to discuss what they have learnt. Mentimeter is used to check understanding and to generate discussion. Although some admitted to struggling to motivate themselves to study beforehand, many enjoyed the approach, with one commenting

‘I love the teaching set-up where we watch [and] learn the content independently and then come together in class to discuss it -this feels like a much more productive use of lecture time.’

Topical sessions are followed by formative feedback sessions building to the summative assessment points. The topical sessions feed into idea formation, while the formative sessions help to hone these ideas and the communication of them. The final summative assessment is a development of the first, so the feedback from the recorded presentations provides an opportunity for students to build on their initial work. This structure is appreciated by students, with one commenting:

‘I really like how the second assessment is directly linked to the first. It […] allows you to directly apply the first set of feedback and see your progress. Because of this, it feels like the module is set-up to really support students’ development.’

6. Review

Some units in Psychology operate a system for groupwork whereby some marks are allocated by the other students in the group. This is a process known as ‘peer review’ and, following student feedback, may become a feature of this unit as well. Currently, however, any peer review takes place in a purely informal way, as students work together to create their research pitches. More formal reviews of progress come in the form of tutorials where tutors take on the role of mentors who have more knowledge of the process of bidding for funding than the students do. The first tutorial is a fairly informal opportunity for feedback and a narrowing down from two topics to one. The second tutorial gives more in-depth feedback on a particular idea, and again, is formative, while the third tutorial gives an opportunity for feedback on a summative piece of work (the recorded presentation regarding the final research idea). It’s value is maximised by being used to give formative feedback, as pointers are given for how to translate that verbal presentation into an individual written submission.

Conclusion

The skills the students learn from this unit are many: problem solving, collaboration, budgeting to name but a few. They are also taught self-reliance: given the creativity and specificity required in developing a bid for applied research these are not tasks that can simply be delegated to GenAI. This approach to designing a unit can also ultimately produce more employable, happier students.